The Night I Lived: Landmines, war and journalism. One close encounter with religion, death, and victory

By Nate Thayer

Excerpt from Sympathy for the Devil: A Journalist’s Memoir from Inside Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge.

(Copyright Nate Thayer. No reproduction or dissemination in whole or in part without express written permission of the author)

By Nate Thayer

It was after midnight, before I was to be picked up before dawn by Thai military intelligence to be escorted into Cambodia to accompany guerrillas on a mission to attack and seize a Cambodian district capitol town.

It was monsoon season. As always, I was carefully preparing my equipment. There was an art to fitting everything I might need into a light backpack with lots of pockets and readily accessible under pressure. There were separate Ziploc bags for different speed film, for each Nikon lens, my two Nikon camera bodies, a point and shoot camera (what we then called a “drunk proof” or “idiot camera”), for an extra pair of dry socks and other dry clothes, a small medical kit, notebooks, a flask of whiskey, a poncho, a hammock, extra pens, a carton of cigarettes to give away to grunts on the front line, tape recorder, extra batteries, and more. As always, I never knew how long I would be gone for or what I might encounter.

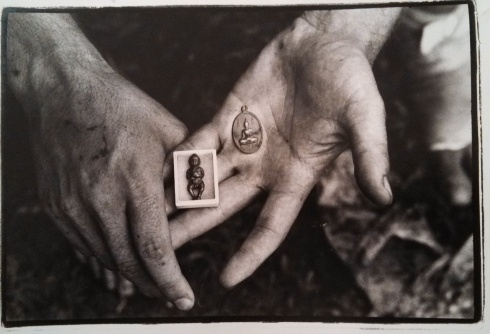

There was a knock on my door, and the manager of my small guesthouse where I lived in the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet, a young boy of 17, entered . Ghung, who I had taken under my wing in the previous months, knew I was going to leave in a few hours on what might be a dangerous assignment. Ghung was very concerned. I invited him into my spartan room and he sat down with a very serious expression on his face. He opened his hands which clutched two Buddhist amulets.

“I want you to take these with you. Wear them around your neck. If you are respectful to them, they will protect you from danger,” he said. The one on the left, pictured below, is an effigy of a dead baby fetus. He warned me that I should not be afraid if it talked aloud to me. The powerful one, he said, was that image, the Kuman Thong. “This will make sure you don’t die”, he said, if I treated it with a reverence.

Ghung clearly did. “Only wear it around your neck and don’t be afraid. Sometimes it will talk to me.”

The Kuman Thong effigy is revered in rural Thailand and Cambodia by many Buddhists, but it is Animist, not a traditional Buddhist practice, more “black magic”, or necromancy. Kuman Thong was created centuries ago by surgically removing the unborn fetus from the womb of its mother. The child’s body was roasted accompanied by chants. original Thai Buddhist texts say making a Kuman Thong amulet requires removing the dead baby from the mother’s womb, followed by a ritual of the baby cooked until dry. This process must be finished before dawn.

“Kuman Thong” means “Golden Baby Boy”. They say if you have a good relationship with your Kuman Thong, you will not have very bad things happen to you.

Ghung’s heartfelt gift had not gone through such an involved process, but it represented. to him, the same power. They are widely believed, in rural Thailand and Cambodia, to be very powerful, protecting one from danger, even bullets bouncing off of you.

Ghung was a very sweet and intelligent boy and we had become friends. I thanked him respectfully, because I knew he was very sincere and serious, but I didn’t really believe him. But it was touching.

I wrapped the amulets in my traditional Cambodian scarf and wore them around my neck when I departed for the Cambodian jungle, before dawn broke, riding shotgun in an unmarked Thai military pickup truck.

We arrived at a secret Cambodian guerrilla base in the jungle just over the Thai border and hour later. The guerrillas were gathered, waiting for me, heavily armed and sporting a dozen new CIA supplied Yamaha 250CC dirt motorcycles. They also had a new powerful secret weapon that the government was unaware had been clandestinely delivered to their enemies the days before. We left the guerrilla base before dawn for an arduous trek through monsoon soaked ox cart paths that snaked through the jungle, led by the convoy of dirt bikes, one of which I was riding shotgun on.

Advance teams of troops were ahead and behind us.

The guerrillas had two new weapons; the German made Armbrust 69 mm shoulder fired one time use anti-tank weapon and the Swedish Carl Gustav 84 mm anti-tank weapon. For ten years, the government had tank superiority. For a decade, once the government tanks broached the front line positions, the guerrillas had no effective weapons to stop them. For years, the guerrilla commanders offered a 50,000 Baht ($2000) reward to any soldier who could stop a tank prior to that day. Their weapon was a B-40 rocket propelled grenade launcher, which required one to get within 20 meters of the tank and aim it so it hit the undercarriage of the tank and took out the tracks to halt its advance. More often than not, the guerrilla would be killed attempting to do so, and if he was lucky enough to survive, it was likely he would be wounded by his own shrapnel backwash from firing the RPG from so close.

This time was different.

We entered the first government held town and immediately destroyed three tanks. The German and Swedish weapons, covertly supplied through Singapore, penetrated the tanks armor but the round would not explode until it was inside the tank, vaporizing the 3 or 4 man crew instantly. I took pictures of their incinerated, burnt corpses still sitting in the drivers seat and manning the tank turret gun, the twisted carcass of the feared armoured T-54 Soviet tank smoking and twisted and neutralized.

We captured that town within an hour.

The government troops fled in sheer terror, the psychological impact and confusion of knowing they no longer had tank superiority changed the face of the war that day.

Within two hours we advanced without hesitation and had captured the district capitol of Thmar Puok.

There, we destroyed 4 more tanks defending the perimeter of the sprawling city.

The guerrilla’s had a celebratory lunch in the former Vietnamese military headquarters, the former only school house in the city and the only concrete building. Graffiti spray painted on the inside walls read in Vietnamese Roman script: “Long Live the Communist Party of Vietnam!”

This was 30 kilometers from the Thai border, more than 500 miles from Vietnam.

It was the first district capitol seized by the guerrillas during the long 12-year war. Government troops, terrified young boys who didn’t care a whit about politics and were conscripted, like all troops on both sides of the war, surrendered by the hundreds, along with their Russian jeeps and transport trucks and weapons.

We drank lots of whiskey in the mid day sun. The people I was with were very happy. Other people, not so much.

For the civilians, none were happy. They were satisfied, like most Cambodian’s, if they did not die, their daughter was not raped, their life possessions not looted, and their water buffalo not stolen.

It was a big story, I knew. I had very good pictures and an exclusive eyewitness account.

We toured the new liberated zone of dozens of villages with no electricity, schools, running water, or hope. This stretch of real estate, for a very, very long time, only knew war.

Then we, after 12 hours, began the return trip to the sanctuaries of the rear bases straddling the Thai Cambodian border, as dusk began to fall, west, towards the Dongruk mountain escarpment far on the horizon marking the border.

The heavy, daily late afternoon monsoon rains had begun.

I was eager to file my story and pictures, which would be, still, many hours away. I still needed to cross out of the jungle, be transported back across the border to Thailand, and down 60 kilometers to the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet.

From there, I would call the Associated Press office in Bangkok and dictate my story by landline telephone.

Ghung, the sweet and cocky 17 year old boy, who had given me the Buddhist amulets late the night before, would always, for months now, push the button on a stopwatch and time my calls and charge me by the minute.

The undeveloped photographs, still on 35 mm film, would be given to the long distance bus driver of the commercial bus company which made a half a dozen trips through the day and night from Aranyaprathet to Bangkok. We would give him no money for fear he would then take the film and sell it to local Thai papers. In Bangkok, an AP messenger on motorcycle would be dispatched from the AP office and meet the bus at the bustling Moenchit bus terminal. There, they would exchange cash for film and he would return to the AP office, where the film would be souped and developed. A few pictures would be chosen and put on a roller and sent over telephone lines to Tokyo and New York. From there they would be transmitted to AP customers worldwide. To get story and pictures out from when they were taken to when they were seen and read could often be days.

But this day it didn’t work out, as it really never did, as planned.

We began the motorcycle ride on our CIA dirt bikes through the uninhabited savannah and jungle, headed west towards Thailand. Bombs and gunfire were everywhere. This area had been under government control when dawn emerged earlier that day. It was, in reality, now under control of no one, but the government had fled. The guerrilla’s had never been here before.

Then the motorcycle convoy of a dozen or so got separated. The dirt tracks were a meter deep in mud. We got separated. Then our motorcycle broke down. Dusk was rapidly approaching. One guerrilla stayed with me. We finally abandoned the motorcycle and began walking west towards the silhouette of the Dongruk Mountains still a dozen miles to the west. That was Thailand and that is where I wanted to be.

“Are there any landmines around here,” I asked the young guerrilla grunt.

“No. No landmines,” he replied

“Where are we,” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Well, if you don’t know where the fuck we are, how the fuck do you know there are no landmines? I asked, now tired, dehydrated, and hungry.

It had been 12 hours since we left the guerrilla base on motorcycles and seized a couple hundred square kilometers of territory. Many, many were dead. That didn’t much bother me. I had not eaten all day. That didn’t much bother me either. I was dehydrated. That made my mind fuzzy. But, mostly, I wanted to get my story and pictures, which I knew would be a minor scoop in the world news, out, safely.

We entered a thicker jungle and bushwhacked ourselves through by hand. We did not know where we were. It was now dark. There were no longer front-lines defined. No one knew what territory was now controlled by the enemy or friends. As far as I was concerned, there were no friends and there was no enemy. I only wanted my pictures and story to get out.

Then we heard the sounds of trucks idling ahead in the jungle.

That was not a good sign. The guerrilla’s I was with—troops of the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front, did not have any trucks.

We halted. We moved slowly through the light forest and peaked through the trees and foliage.

There idling on an oxcart path, were two Soviet Zil transport trucks with several Cambodians in government uniform carrying Soviet issue AK-47’s.

My lone guerrilla companion turned to me, after a long period of silence, and said: “I think they have defected to us.”

“What the fuck do you mean ‘You think they have defected?” That is not fucking good enough! They either have defected or we are about to be dead or become prisoners of war.” I was, honestly, ready to surrender if the latter was the case.

He had a look of fear and uncertainty in his eyes. That scared me even more. “You wait here. I will go check,” he instructed me, failing in his attempt to give the impression he was in control of the situation.

He tried to be quiet as he pushed aside the forest brush and not alarm the armed men in government uniform in government military trucks.

I waited, crouched, decidedly not comfortable in the savannah. My guerrilla guide returned with a smile on his face. The armed men and vehicles had, indeed, defected in the previous hours.

I was ecstatic. It was dark. We were lost. Our motorcycles had broken down and been abandoned. It was rainy and muddy and hot. I was hungry and we had no water. We were in territory under unclear control. Now we had a truck and we would be back in Thailand within an hour.

I emerged from the jungle and was greeted warmly although with the concomitant, quizzical look that is directed towards animals in a zoo.

There were about a dozen troops in the jungle clearing with two trucks. Some were guerrillas and some were freshly defected government troops. We all piled into one truck. The driver was a government soldier hours before. Now he was a guerrilla. Three of us were in the front seat, myself squeezed in the middle, between the driver and n impressive fat guerrilla officer. About a half dozen troops were in the open back carriage of the 2 ½ ton Russian military transport truck.

We were laughing and giddy as we slowly negotiated the mud soaked, deeply rutted ox cart path, headed west, towards Thailand. The dim silhouette of the Dongruk mountain escarpment still visible under the moonlight about ten miles to the west.

I remember being scrunched up tightly between the fat guerrilla commander and the skinny young boy government conscript, now a defector, in the driver’s cabin of the Zil. I was sitting in the middle. I was in a very happy mood. I had great pictures and a great story and I was the only journalist there and I was now in a truck being driven towards a safe place where I could transmit them to the few interested around the world. I remember chatting to the driver, smiling and laughing. He was happy to, mainly because he was not dead, a fact I am sure he was concerned about at the start of that day.

I loved this life.

We had been driving only a few minutes and then something–in an instant–terrible, something life altering, and for some, life extinguishing happened.

The sound was so profoundly loud that I could not hear it. My eardrums were blown out. The concussion of the explosion was so great my brain shut down. I remember the liquid in my body became so heated I could feel it simmering near boiling. I could hear my blood boiling, gurgling from what seemed like heat. I felt my brain being tossed around like a rag doll bouncing off the insides of my skull.

Our 2 ½ ton truck was thrown in the air several meters and, luckily, hit the side of a tree, and bounced back down, landing upright. Actually, I don’t remember that part. I saw it, afterwards. It looked like a shredded child’s toy Tonka truck.

We had driven over two Chinese anti-tank mines.

Specifically, our left front tire, which was less than 1 ½ meters from where I had been sitting.

This is very Cambodian. One does not need two anti-tank mines to blow up a tank. One will do. But, for good measure, just in case, the guerrilla’s had placed one on top of another. The mines were placed by the guerrilla’s themselves. Because they had no vehicles—until that morning.

We had just driven over our own landmines.

I don’t know how long I was unconscious.

I do remember waking up that night, with clarity and vividness, that startles me in my sleep and jolts me awake, regularly, now many hundreds of nights and some days, to the present, years later, in a mixture of unspeakable fear and grief and confusion and sadness.

There was a severed leg lying across my face. I held the leg up and looked at it. It was not connected to a body.

I was in the remnants of the engine compartment of the truck, its tattered carcass spread meters across the muddy jungle ox cart path.

I needed to know whether it was my leg I was holding in my hand. But I was very scared to find out. I reached down and ran my hand over my left leg and it was still attached to me body. I did the same with my right leg. It, also, was still attached to my body.

I had no idea what happened. I looked around me.

A few feet away was the young Cambodian truck driver, moments before with whom I was laughing and smiling and chatting. Life, for both us, would be, from that moment on, very different. His would be much shorter than mine.

He was sitting up, with a look on his face of raw terror and amazement I will never, ever forget. He was holding tightly the stump of his thigh, eyes locked, fixed, wide open, staring at what was no longer there. He did not panic. He didn’t seem in pain. He cried—no he moaned–loudly, but in words profoundly mournful.

He only called for his mother.

“Mother, please help me!” he repeated over and over and over and over.

I extricated myself from the engine and went over to him and held him in my arms. “You will be OK,” I lied. “Everything will be fine.”

For perhaps ten minutes, he called for his mother, staring in utter terror and horrid curiosity, his mind racing over, I suspect, his brief past, perhaps his never realized hopes, and his now very, very brief future, while grasping tightly the shredded stump of his muscle and bone and meat in his hands, the end of what was his leg, now within easy reach of his clutching hands.

And then he died on this irrelevant, muddy jungle dirt ox cart path, in the rain, at night, far from his mother. Probably, no one, other than the half dozen of us there that night who remained alive, to this day, knows how and where he died. He just never came home. There are millions of Cambodians whose loved ones simply never came home and they don’t know why.

We left him, dead, on the dirt path, in the dark, alone. I am sure, no one amongst us even knew his name.

The man who was sitting to my right, the fat guerrilla commander, before the driver died, was angry.

He had taken shrapnel to his head. It penetrated his brain. There was a gaping hole on the side of his skull, above his ear, leaking increasing amounts of blood and other coloured liguid.

I remember him cursing the truck. He got up and he kicked the side of the truck with a ferocious boot and yelled and blamed the truck. Who else was there to blame?

Then he died, too, falling on the mud path, on his face.

We left his body there as well.

After I had fled in slow motion the dying, legless driver, another man, lying down, prostrate, who I thought was dead, bolted upright.

He jumped up and yanked his pants down and, terrified, grabbed hold of his cock and balls and inspected them to make sure they were intact.

That made sense to me and I immediately did the same. I later learned this is a common reaction to the freshly wounded in war.

I remember asking him: “What just happened?” I had no idea. I had no idea we had run over a landmine. I did not understand why, in the dark, and mud and rain there were people dying and suffering.

“”We hit a landmine,” he said, with no discernible emotion.

Then, strangely, I became obsessed with locating my fil, my cameras, my notebook from the wreckage of the debris of the truck and human carnage littering this irrelevant jungle patch, which, really, was of importance to no one, save those of us who died, or didn’t die, there that night. I became obsessed and started sifting through the metal and mud looking for it. Two other surviving troops came over and helped me. We found my Nikons and lenses and film and small,little backpack next to the bodies and under the remains of the truck. They had survived unharmed. I was greatly relieved.

Most everyone that night was killed, but several of us were not. Two were severely wounded. We cut two tree branches and attached hammocks to them, and two guerrillas carried the badly wounded through the night, in the rain and dark, for three hour, for 7 miles, a silent, sad trek, everyone lost in their own thoughts, to the nearest guerrilla base.

There, 7 miles away, they had felt the earth shake from the explosion from the landmine that was planted under the dirt less than 2 meters from me that night.

We began a long silent, sad walk.

I didn’t know that bones were sticking out of my leg until I stepped in a mud hole on that walk and a jolt of pain went from my leg to my brain. I didn’t know that I had shrapnel in my head until I tasted blood dripping into my mouth and wiped my hand over my face and looked, in fear, as it was covered in bright crimson fresh liquid.

I didn’t know I had permanent brain damage. Or that my ear drums were burst, or that my sternum was broken. Or that my liver was dislocated. And other stuff.

I just walked. Because we had no choice.

We arrived, hours later, at the guerrilla base. They knew we were coming. They piled us wounded into the back of a pickup truck and took us to a CIA funded guerrilla operating theatre in the jungle. It had a generator to provide electricity for an antiseptic operating room. There was an air conditioner in it. But we were put into an open air thatch roofed room. The loud din of a chorus of frogs croaking in celebration of the heavy monsoon rains, along with crickets, was soothing, but was so loud one had to speak louder to be heard.

A dozen or so soldiers, all on crutches, their freshly bandaged stumps of legs covered in bright red fresh blood, their legs and arms and some one or both of each, gathered and stared at us, the new arrivals to their new world.

I was placed on an elevated military cot. Next to me was the most badly wounded soldier. The kind French trained Doctor spoke softly and touched and poked me, my badly wounded neighbor on the stretcher next to me, and one other severely wounded guerrilla.

Then two soldiers walked in with a chainsaw, headed towards me.

I had bones sticking out of my feet. I jumped up like an Olympiad on methamphetamines and screamed in at least three languages to get the fuck away from me. I was forcibly restrained and reassured that the chainsaw was not destined for me. It was for the man next to me in the stretcher. They were massaging his heart. His leg was attached by a few strands of ragged tendons to his torso. he was not conscious. The medics, who, in truth, only had training in amputating limbs, cranked it on and cut his leg off with no anesthesia, two feet from me. I stared emotionless at this. I was drained of any reserves of emotion by then.

I watched, in retrospect, with a calmness fueled and mitigated, I guess, by the context of the evil of that night. He died not so long afterwards.

They took me to the operating room. They took pieces of metal out of my legs, my torso, and my head. They sewed it up. They did their best.

Honestly, I felt very little pain, even then. I had just been blown up I then walked 7 miles with bones protruding from my foot, dozens of holes in my body, pieces of metal embedded in my head my torso, my legs, my feet. I had several broken bones. But in the coming days, for weeks, I would not be able to move from the pain.

Despite the unpleasantry of the previous hours, oddly, I was fixated, oddly, on one thing–to get my photographs and story to the Associated press office. I knew then I could relax, my job done.

I repeatedly asked to be taken back the 60 kilometers to the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet. I needed—not wanted—I NEEDED—to file my pictures and story. In the darkest hours before dawn, I was driven by Thai military intelligence in an unmarked truck back to my hotel.

I was bandaged. I was confused. My whole body hurt by then.

My good friend, Philip Blenkinsop, the photographer was staying in another room in the sparse ten room ground floor motel. I knocked on his door. It was before dawn.

He opened the door and stared silently for a few seconds. Philip, who I love dearly, didn’t say “What happened to you? Are you OK?”

He said, and I won’t forget these words: “Don’t move, mate, Great pics. Let me get my kit.”

I felt comforted, as if I was now home and out of danger and with my people. He took these, and other pics.

The young boy, Ghung, the 17 year old Thai hotel manager, came to the room a while later. He had a serene and loving look on his face. He looked me in the eyes and said ‘I told you they would protect you.”

Ghung knew he had saved my life that day. And I was pleased he believed he did. His black magic dead fetus was still wrapped around my neck.

Both he and I were very thankful and quite satisfied with the day, for different reasons.

Later the commander and chief of the guerrilla army came to my hotel room with a dozen roses. I liked this man. He smiled and chuckled and said: ” I told them not to drive down that path” and he handed me the flowers.

But the memory since has never left me, and never will leave me with any sense of peace or conclusion. I am not sure this story can be adequately conveyed. But that is the best I can do, today, 22 years later.